Egyptian Mummies: Exploring Ancient Lives is the new exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Montreal, done with the collaboration of the British Museum. We have a good macro-understanding of ancient Egypt through its architecture, art, economics, and culture from the early dynastic period (3100 b.c. to 2686 b.c.) to the Roman period (30 b.c. — the fall of Antony and Cleopatra — to a.d. 395). Elusive, though, are the particulars of everyday existence such as life span, health, diet, aging, and burial practices, including the process of mummification.

Egyptian Mummies is the latest word on these subjects. It’s a fascinating mix of art, science, and the lifestyles of six Egyptians whose mummies date from 900 b.c. to a.d. 180. Technology allows us to see inside the living body, saving countless lives. It also opens to us the doors of the dead. It appeals to the history-minded, the superstitious, the horror-obsessed, and the voyeuristic in all of us.

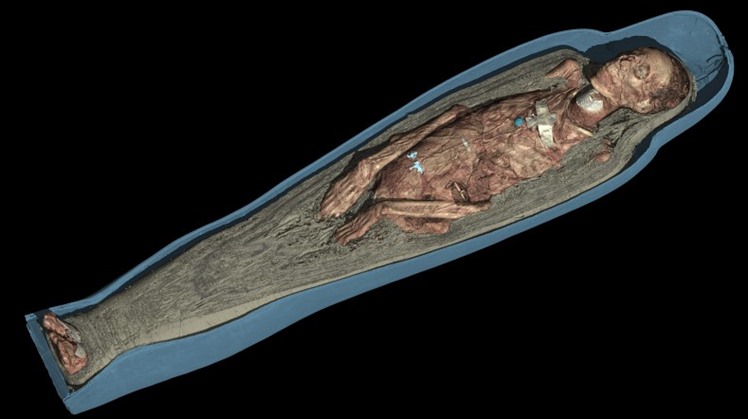

Today, computerized tomography (CT) scanning makes it possible to see and interpret an immense, long-hidden trove of information, thanks in part to the British Museum’s centuries-old ban on unwrapping its mummies. A policy respecting the dead left the mummies undisturbed, or no more disturbed than they already were, having been exhumed and hauled to cold, damp Britain. They don’t exactly sing and dance, but science’s capacity to render layered, 3-D images makes the mummies seem very human. They spill lots of beans on how they lived then. A funerary boat from 1985–1795 b.c., the first object in the show, tells us we’re about to be transported.

Model of a funerary boat, 12th Dynasty, about 1985–1795 B.C.E., provenance unknown, sycamore fig wood, EA 9525. (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Tamut (in the feature photo at the top of the article) is my new best friend. From the inscriptions on her inner coffin, we know she started life as a high-ranking priest’s daughter from Thebes — modern Luxor — living around 900 b.c., and she ended as “the Lady of the House,” having married someone rich. Mummification practices evolved over centuries, but in those days, and scanning shows this, her brain was removed and her skull packed with textiles. Her organs were removed, embalmed, and bundled in bags placed in her chest cavity.

By 900 b.c., Egypt’s imperial days were gone, but it was just reaching the zenith of mortuary science. Then, to qualify for a happy afterlife, the body needed to look as hale and hearty as possible and kept as intact as possible. So the organs were salvaged, but the organ bundles and the textiles in the skull were arranged both to give Tamut a full-figured look and to disguise disfigurations that occurred during embalming. The goal wasn’t so much to create a good likeness of the dead but to transform the once-living person into a servant of Osiris, the multitasking god whose portfolio included fertility, agriculture, life, the afterlife, and resurrection.

Scanning shows the size and design of the jewelry adorning her body, including gold nails on her fingers and toes. Cleverly, the curators made 3-D models of her jewelry displayed in a case. Tamut was mummified with a large sheet-metal falcon ornament and a scarab over what was once her heart. It’s engraved with a spell preventing the gods from discovering the misdeeds in her heart when judgment time comes. Incidentally, scans also show the arterial plaque that probably killed her.

After centuries in her grave, Tamut traveled to London light. Her elaborately decorated inner coffin, made of a material like papier-mâché, is impressive. She probably had two outer coffins that disintegrated. The coffin that’s left is gilded and painted with winged gods, beetles, falcons, panthers, and inscriptions. Her father was an “aq” priest, which meant he had access to the most sacred rooms at Karnak. She was, literally, “5’2″, eyes of blue,” though the blue is the color of agate stones placed in her eye sockets. Hardly a flapper, she was buried in dignified luxury, and laid out anew in Montreal in fine form. The curators are good storytellers, which is what a good curator needs to be. The objects give us a documentary and aesthetic feel for Tamut and her world.

Irthorru, Nestawedjat, a young temple singer, an unknown two-year-old child, and a young man from Roman Egypt round out the merry band. The Roman mummy, from about a.d. 150, sports at the head of his coffin a lifelike encaustic portrait of a beardless young man with dark, wavy hair and wide eyes in a white mantled tunic. He was in his late teens when he died. While Egyptian religious concepts of the afterlife didn’t change much, death fashions did. With the portrait, his mummy shows the incursion of Roman realism in painted or sculpted portraiture. Whether an emperor or a lesser form of humanity, Romans didn’t idealize. Roman portraits look like real people.

I did wonder in walking through the show how the curators would indulge the Canadian reverence for diversity, equity, and inclusion. These mummies were all part of Egypt’s 1 percent, after all. No affirmative action or identity politics was possible. At the end of the show, a wall panel entitled “Diversity” assured us that all was not lost. It’s vague but seemed de rigueur. It notes that Greeks and Romans were abundant in Egypt and that painted shrouds depicting a single figure, probably the corpse, and realistic portraits at the head of the coffin showed “diverse” taste in art, though I’d call it simply the dissemination of new style, which is really part and parcel of the history of art.

The young child’s coffin has a gilded, molded plaster mask with stylized hair and a face that’s not a portrait — it’s almost a hundred years earlier that the Roman mummy of the young man — but takes a stab at looking sculpturally lifelike, with a 3-D face. He holds a bouquet of red molded plaster flowers. The archaeologist who discovered the mummy described him as “splendaciously got up.” Nice touches include molded plaster feet with sandals on top of the foot-case and, under the foot-case, paintings of two men in chains. The image suggested the deceased had the power to tread enemies underfoot. Painted on the back of the plaster head is a scene of a nude child flanked by two gods pouring water on his head. The gods hold his hands, as if to assure him he has nothing to fear.

There are good sections on dental health — teachable moments on where failure to floss will lead you — and diet. Irthorru ate well — he was a high priest with healthy bones and teeth with usual wear and tear. Our young Roman friend was probably fat, judging from his pelvis and knees, and ate too many sweets, judging from his prematurely rotted teeth. I surmise that by a.d. 150, the Roman Empire was going to the dogs, its young overfed, given to junk food, and definitely not doing their push-ups. Egyptian sculpture in the exhibition depicts scenes of family life. Ancient musical instruments give context to our temple singer.

It’s a material culture show, and I didn’t expect the majesty of King Tut, the Rolls-Royce of gold-bedecked graves. It’s an archaeology exhibition and gives people context and perspective. It drives home the not-so-clearly-understood fact that the world didn’t begin the day the first Millennial graced the planet.

On the installation, I thought the labels on the cases displaying the coffins were impossible to read. They were placed flat on the side of the cases, at wheelchair level. A beveled label would have been more readable. The entrance to the show was decidedly unceremonial, signaled only by a desk hawking audio tours, with no signage. The big gallery with the coffins was, I thought, too packed with objects. While the museum’s newish modern building is sleek and attractive, the show is in the old building across the street, which is accessed only by a long trek underground, down stairs, up stairs, through winding corridors. By the time I reached Egyptian Mummies, I felt as if I’d traveled the length of the Nile. These are quibbles, though. The building is the architect’s fault, not the curators’. The exhibition is wonderful.

3

The Montreal Museum of Art does amazing shows. Over the past 20 years, the museum has shown daring, imagination, incisive scholarship, and flair. Its show on Walt Disney’s debt to Old Master and 19th-century art was the best show I’ve seen, ever. I loved the Maurice Denis retrospective and shows on Dorothea Rockburne, Tom Wesselman, and Marc Chagall. Its 2017 show, Revolution, treated the late 1960s through painting, music, design, fashion, and film.

I can’t say Revolution was magnificent. With 700 objects, it was an excess of abundance that suited the time. It re-created and stylized a repulsive period, revolting in almost every permutation, to give the show’s title a twist, but I still liked it. Montreal is very different, though it’s as close to my home in Vermont as New York and Boston are. The show gave me a “not American” — dare I say “French” — view of the late 1960s, which added a perspective different from mine. The Montreal Museum consistently challenges the mind and never wanders beyond the realm of the aesthetic. It’s an approach I’d suggest to American museums, many of which are too timid, boring, faddish, and preachy.

Article originally published on nationalreview.com and written by BRIAN T. ALLEN an art historian.

Tue, Jan. 21, 2020

Tue, Jan. 21, 2020