The University of Copenhagen in Denmark is home to a unique collection of Ancient Egyptian papyrus manuscripts.

A large part of the collection has not yet been translated, leaving researchers in the dark about what they might contain.

“A large part of the texts are still unpublished. Texts about medicine, botany, astronomy, astrology, and other sciences practiced in Ancient Egypt,” says Egyptologist Kim Ryholt, Head of the Carlsberg Papyrus Collection at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

An international team of researchers are now translating the previously unexplored texts, which according to one of the researchers, contain new and exciting insights into Ancient Egypt.

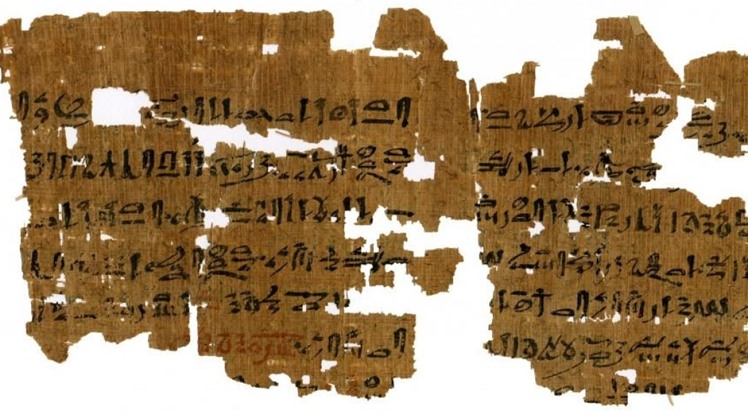

This little piece of papyrus is believed to contain a type of oracle question. The author has written two possible outcomes for a situation and asked the gods to indicate which one was the truth. (Photo: The Papyrus Carlsberg Collection/ University of Copenhagen)

“It’s totally unique for me to be able to work with unpublished material. It doesn’t happen in many places around the world,” says PhD student Amber Jacob from the Institute for the Study of The Ancient World at New York University, USA. She is one of four PhD students working on the unpublished manuscripts held in Copenhagen.

The Egyptians knew about kidneys

Jacob’s research focusses on the medical texts from the Tebtunis temple library, which existed long before the famous Library of Alexandria, up until 200 BCE.

In one of the texts, she has found evidence that Ancient Egyptians knew about the existence of kidneys.

Sofie Schiødt in front of a 3,500-year-old medical papyrus. (Photo: Mikkel Andreas Beck)

Sofie Schiødt in front of a 3,500-year-old medical papyrus. (Photo: Mikkel Andreas Beck)

“It’s the oldest known medical text to discuss the kidneys. Until now, some researchers thought that the Egyptians didn’t know about kidneys, but in this text we can clearly see that they did,” says Jacob.

The papyri also reveal insights into the Egyptian view on astrology.

“Today, astrology is seen as a pseudoscience, but in antiquity it was different. It was an important tool for predicting the future and it was considered a very central science,” says Ryholt.

“For example, a king needed to check when was a good day to go to war,” he says.

Astrology was their way of avoiding going to war on a bad day, such as when the celestial bodies were aligned in a particular configuration.

Egyptians’ contribution to science

The unpublished manuscripts provide a unique insight to the history of science, says Ryholt.

“When you hear about the history of science, the focus is often on the Greek and Roman material. But we have Egyptian material that goes much further back. One of our medical texts was written 3,500 years ago when there was no written material on the European continent,” he says.

Analysing this 3,500-year-old text is the job of PhD student, Sofie Schiødt from the University of Copenhagen.

One side of the manuscript describes unusual treatments for eye diseases, says Schiødt.

Papyrus text discovered in Germany

The other side, describes the Ancient Egyptian equivalent of a pregnancy test and scan.

“The text says that a pregnant woman should pee into a bag of barley and a bag of wheat. Depending on which bag sprouts first reveals the sex of her child. And if neither of the bags sprout then she wasn’t pregnant,” says Schiødt.

Her research reveals that the ideas recorded in the Egyptian medical texts spread far beyond the African continent.

“Many of the ideas in the medical texts from Ancient Egypt appear again in later Greek and Roman texts. From here, they spread further to the medieval medical texts in the Middle East, and you can find traces all the way up to premodern medicine,” she says.

The same pregnancy test used by Egyptians is referred to in a collection of German folklore from 1699.

“That really puts things into perspective, as it shows that the Egyptian ideas have left traces thousands of years later,” says Schiødt.

"Every singly contribution is important"

Translating the unpublished texts is important work, according to Egyptologist Hans-Werner Fischer-Elfert from the Department of Egyptology, University of Leipzig, Germany.

“We still have a very fragmented knowledge of the natural sciences in Ancient Egypt. Therefore every singly contribution is important,” he says.

“Today there are still a number of sources that theoretically were known by scientists but still sat dormant in various collections around the world without anyone looking at them in detail. Now the time has come to recognise them.”

----------------

Translated by: Catherine Jex

Article originally published on sciencenordic.com

Tue, Aug. 27, 2019

Tue, Aug. 27, 2019